Trick or Treat: The Science of the Paranormal

This week, The Naked Scientists delve into the paranormal. We'll be asking why so many of us have supernatural beliefs, exploring the scientific origins behind our favourite monsters, and bravely embarking on a ghost hunt... Plus in the news, what dinosaurs and zorro have in common, why swearing could do you some good, and how sugarcane ethanol could help cut global carbon emissions.

In this episode

00:55 - Could sugar help us be greener?

Could sugar help us be greener?

with Professor Stephen Long, Lancaster and Illinois University

The 2015 Paris Climate Agreement saw almost every country promise to try and limit global temperature rise to 2 degrees C above pre-industrial levels. Emission reduction poses a significant challenge, so perhaps replacing fossil fuel use with biofuels, which are renewable and emit less net carbon, may be part of the solution. In a paper published this week, scientists have projected that sugarcane ethanol, a biofuel, produced in Brazil alone could offset net emissions by more than 5%. Katie Haylor spoke to author Steve Long, crop sciences and plant biology professor at the Universities of Illinois in the US, and Lancaster in the UK.

Steve - Sugarcane is almost the most productive crop in the world; it produces a large amount of material. Typically, a field of sugarcane will produce up to about 100 tonnes of cane stem per hectare, and about 25% of that stem is sugar. So that is then cut, transported to a mill, and the sugar juice is extracted. That can then be fermented to ethanol; the ethanol distilled and almost all cars in Brazil are flex fuel. That means they can burn ethanol or gasoline and so that allows the Brazilian consumer to use ethanol in their car, usually more cheaply than gasoline.

Katie - This is already taking place in Brazil. Tell us about your prediction - what's novel about this study?

Steve - The core of it was a new model of sugarcane growth. The model actually uses the physiology of the plant: how it responds to rising temperature, rising carbon dioxide, changing soil moisture. We first tested this under present and past conditions and then used it to project forward to work out what productivity we could get in different areas of Brazil in the future. And we overlaid that on knowledge of soil, existing land usage and so what the potential was to expand the crop.

Katie - Tell us about your findings; can you summarise them for us?

Steve - Our finding was that, particularly if we look at land which is underutilised at present, for example, a low intensity pasture, there is considerable opportunity to expand sugarcane production in Brazil, in fact, more than the area of Texas. This would allow Brazil to, if we look at use of fuels in 2014, to displace about over 5% of current emissions by the period of 2040/2050 despite climate change, despite other pressures on land use.

Katie - That’s a very impressive number over 5%, but would this development have other consequences, for example, on people or animals, the environment, the protected environments in those particular areas?

Steve - Not really. This is land that has already been converted for sugarcane use.

Katie - So we’re not talking about the rainforest or protected areas here, are we?

Steve - No. In our particular study we limited this to land which the Brazilian government has mapped out for legal conversion. So we are not talking about the Amazon, the Pantanal, areas of rainforest that have been mapped out for protection.

Katie - Can you summarise the likely significance of this if it were to be adopted in other countries other than just Brazil?

Steve - Sugarcane actually globally has been in decline because demand for cane sugar has been reducing. For example, we see Hawaii and Puerto Rico in the United States, most of the land that was once used for sugarcane production lies idle today. Much of the Caribbean we see the same story and other countries in the north of South America that land is idle. So, if they were to adopt the technology that Brazil has already developed, we could actually displace considerably more than that 5%. We could then be talking about 10% of emissions. Clearly we need many other technologies to reach the targets of the Paris Agreement, but 10% would be a large chunk.

05:56 - Sending ashes into space

Sending ashes into space

with Dr Chris Rose, Ascension Flights

Now for something that’s a little out of this world - literally! How would you feel about having your ashes scattered in space? Ascension Flights is an organisation seeking to provide exactly this service. To find out more, Izzie Clarke found out why from co-founder and engineer Chris Rose.

Chris - Space inspires awe and wonder in so many people. I think the reason for that is because essentially it is so vast and humans want to explore the unknown and it’s a kind of area that can never truly be explored, so we have a hotspot for space, and I think having your ashes scattered in space really does have a lovely ring to it.

Izzie - Talk us through the science. How are you getting ashes into space and what happens after they’ve been scattered?

Chris - The motivator for getting things high above the Earth and into space that we adopt is very large balloons. Now rockets are very understood in that these can travel very long distances but they need a lot of expensive fuel onboard, a lot of kinetic energy to get it high. It’s quite a violent process and it’s quite a short lived process.

Balloons, on the other hand, offer us the opportunity to have a very tranquil, very controlled ascent over a longer period and that gives us some spectacular results all the same. We can use these to get well into near space - up to 50 kilometres above the Earth so you can see the blackness of space, the thin blue line of the atmosphere, and the curvature of the Earth before the ashes are actually scattered.

Izzie - So this balloon takes the ashes up and then how are they actually then released?

Chris - On board our payload, if you like, which contains our very specifically engineered scattering mechanism which I’ll discuss the details of in just a moment. But the balloon progresses through the atmosphere on its journey into space by using a gas, in this case helium or hydrogen, and the density difference in this gas gives us our buoyancy, so what the balloon is essentially trying to do is to rise up. It’s just when you take a capsule with the some air in under water, it’s trying to rise up above that medium that surrounds it and essentially sit on top of the atmosphere. When it does get into space it no longer has that duality of gases and different density differences to continue on its journey.

It expands throughout its ascent through the atmosphere to the point where when it does indeed burst because it can’t stretch any more, it's going to be bigger than a house. We’re talking close to 15 to 20 metres in diameter so very, very large. Now this is taking all our sensitive recording equipment: our control systems, our tracking equipment because we need to relocate everything after the payload returns to Earth and, of course, our scattering mechanism that contains the ashes.

This mechanism is understanding how high it is above the Earth by talking to satellites and as soon as it reaches its lower threshold, which we programme at an altitude the wish the scattering process to begin. It then tells itself to open up and begin the scattering process. The reason this has taken us a long time and we’ve taken much care to put the engineering in to get it right is because we don’t want this to be ashes just released and above the Earth projected as a sort of big conglomerate. What we want is a beautiful, aesthetically pleasing scattering process that lasts for as long as possible. And essentially looks beautiful but also allows the ashes to be dispersed as widely as possible above the Earth.

Izzie - How long does that entire journey take?

Chris - For an entire flight from the release to the burst, to the landing of the payload again on Earth is about 2 hours 40 minutes. The majority of that is the ascent itself. We opt for about 5 metres per second ascent rate. We obviously take a lot of care to get the maths right and run simulations so we can see exactly what the payload path will be taking, where it will burst, and where is should land again.

The return journey of the payload: essentially there is no atmosphere there to act against the payload or the parachute. So the descent itself is about half an hour because it’s going to be falling at about 300 miles per hour, maybe closer to 250 miles per hour depending on the conditions because, essentially, there’s nothing there to slow it down. But, rest assured, when the payload and the parachute do get down into the troposphere, where the weather systems are, this will slow to a nice gentle descent rate and land where we calculate in an area that’s appropriate.

Izzie - Isn’t this just all falling back to Earth and does that count as pollution? Is there a risk involved with that because aren’t people just essentially breathing in someone’s scattered ashes?

Chris - When we scatter ashes there are sort of loose legislation around what should be done. Although some of these are legalities and some are suggestions the common sense thing is not to scatter ashes in public areas. As you can appreciate, we are very far removed from a public area because we’re actually scattering these in space, so we couldn’t really be abiding by the rules any more than that. But, what happens to the ashed after we have scattered them? Well, these get so dispersed throughout the winds. You could have portions of the ashes being carried in through atmospheric currents to other countries. So, essentially, people being able to quantify and presence of the ash or experience them on any level on the Earth is pretty much statistically impossible.

11:28 - Mythconception - are bats really blind?

Mythconception - are bats really blind?

For our Halloween special, Georgia Mills got her teeth into the old phrase “blind as a bat”...

Georgia - As it’s Halloween, bats are finally getting their moment in the spotlight. But, it’s not like they can see it being “blind as a bat.” Well, no… bats just aren’t blind. Every single species of bad can see to at least some degree, and some of the larger ones have better eyesight that we do. Plus, all of them can enhance their sight with something called echo location where they bounce sound off objects to work out where they are. So, next time someone says you're “blind as a bat,” you can thank them for the kind compliment.

That myth didn’t take too long to bust so I’m going to spend the rest of this segment looking at another myth about these small furry fiends. Because bats have a bit of an image problem - bats are considered diseased, evil, and ugly. Even batman is scared of them. But, do they really deserve their bad name. Let’s look at disease first…

Bats are supposedly riddled with rabies and, while they do carry the disease, according to research in the USA only about 1% of them actually have it. And, in the UK, we’ve only ever found 14 infected bats in the last 30 years. Plus, most species of bats are really uninterested in biting humans; they’ll only really do it if they’re picked up or startled, but it’s true that bats are implicated in some of the most terrifying diseases including Ebola.

They’re social animals and they move around a lot so diseases do move about with them, however, it’s not all the bats fault. As humans spread across the world we’re entering their territories more and more which does increase the chances of contacting them. So, they’re a little bit diseased but not as much as you might think.

Are they evil? Well, mostly they’re gentle and timid. The most villainous bats of history are probably the ones used in a bat bomb and it wasn’t really their choice. In world War II there was this idea to drop a bomb full of bats, each with their own bomb on timer. The bats would flee from the larger bomb, roost in houses and then, unfortunately for the bats, explode. Which would set of hundreds of fires simultaneously in a huge area. Although about 2 million dollars and probably a bats were sunk into the idea… it never saw combat.

Some species of bat are actually very altruistic. If a bat notices its neighbour hasn’t had it’s nightly meal it will very kindly vomit some of it’s own dinner into their mouth. I bet your neighbours wouldn’t do the same for you. And they provide us with hugely important services - bats do pest control for free. Chomping ups some of our most irritating insects saving farmers billions. Plus, they like mosquitos which are themselves a transmitter of malaria. Fruit bats poop seeds far and wide, which is key to keeping our rainforest healthy, and many species are pollinators just like birds and bees so are vital to maintaining the food chain.

And finally… bats just aren’t ugly. Depending on what they like to eat they’ve got very different shaped faces, but they’re all good looking in their own way. If you still think they look a bit scary, look up a photo of the Honduran white bat. These look pretty much exactly like a piece of cotton wool with a pig face, and they build tents out of leaves and snuggle inside together - hardly the stuff of nightmares.

Whilst bats themselves aren’t the stuff of nightmares, they’re facing their own at the moment. Human activity and a disease called white nose fungus is wiping out huge numbers of them which, in turn, can damage our ecosystems and our food security. So bats need our support… not our fear.

15:04 - Discovering dinosaur colour patterns

Discovering dinosaur colour patterns

with Fiann Smithwick, University of Bristol

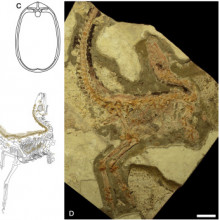

As bats can’t give us the chills, perhaps it’s time to talk dinosaurs! Theropods, like the T.rex, were two legged dinosaurs with feathers. An amazingly-well preserved fossil of a small, long tailed theropod has led researchers at the University of Bristol to reveal its colour patterns. By reconstructing the likely colour patterning of the Sinosauropteryx, from a fossil found in China, researchers have shown that it had multiple types of camouflage which helped it to avoid being eaten in a world full of larger dinosaurs. Fiann Smithwick gave Izzie Clarke an idea of what this Theropod would’ve looked like…

Georgia - Now, as bats can’t give us the chills, perhaps it’s time to talk about everyone’s favour monsters - dinosaurs! Theropods, like the T.rex, were two legged dinosaurs with feathers. An amazingly-well preserved fossil of a small, long tailed theropod has led researchers at the University of Bristol to reveal its colouring. By reconstructing the likely colour patterning of the Sinosauropteryx, from a fossil found in China, researchers have shown that it had multiple types of camouflage which helped it to avoid being eaten in a world full of larger dinosaurs. Fiann Smithwick gave Izzie Clarke an idea of what this Theropod would’ve looked like…

Fiann - Theropods are the famous meat eating dinosaurs so the classic is, obviously, T.rex (Tyrannosaurus rex). And this little guy Sinosauropteryx was a small theropod - it was only about a metre long, or the largest fossil is around a metre long and it had an exceptionally long tail. We know it was carnivores: it had typically carnivore or meat eating teeth, but also, fantastically, one of the fossils has a complete lizard within its stomach. But now, thanks to the work that we’ve done, we can also say what kind of colour it was.

Izzie - Oh my goodness! How on earth can you work this out because we are talking about millions of years ago?

Fiann - It is incredible. This particular dinosaur is from a fossil formation that’s 126 million years old so it’s pretty impressive we can work out the colours from it, and that’s because of the pigment that gave the animal it’s colour in life. This is melanin which is the same pigment that we have in our skin and hair, and animals have in their hair, and birds have in their feathers. It’s a very stable molecule so it’s very resistant to decay, which means we see it in quite a range of fossils where we have good soft tissue preservation, and that allows us to look at the colour patterns of these animals. And, importantly, there are areas on this fossil that don’t have these pigmented feathers preserved and that’s not because these were naked areas in life that didn’t have any feathers, but we think it’s because only the pigmented feathers preserve due to the fact that melanin is so resistant to decay.

Izzie - Why are all these different colours and pigments so important?

Fiann - It’s important because we can determine some key colour patterns on the dinosaur that we know exist in modern animals. And that allows us to make comparisons and attempt to understand the behaviour of the dinosaurs, and also why it may have evolved these and what that says about the environment that it lives in.

One of which was countershading. This is having a dark back and light underside; it’s a form of camouflage. So blending in better to the background if you have a dark back and you’re being viewed from above, this will clearly blend in better to the ground. And if you have a light underside and you’re viewed from below, this can balance against an illuminated sky. But also, importantly, countershading can make an animal look flatter and this is the principle that we used to reconstruct the likely habitat that Sinosauropteryx was living in. That’s because different environments have different lighting and, therefore, you need different colour patterns in order to counterbalance this lighting.

Izzie - I read somewhere that also has a “Mask of Zorro”- like look. This sort of dark black banding across its eyes. How does that work?

Fiann - It does indeed. We could see the distinctive areas of pigmented feathers around the eye that would probably have formed a solid stripe that we refer to as a “bandit mask.” One of the likely functions of this, which is particularly seen in modern birds, is as another form of camouflage. This time actually masking the presence of the eye. Eyes are a really key cue for both predators and prey to avoid being eaten or to avoid being spotted so they can actually catch other animals.

But also having this dark stripe may also serve as a form of anti-glare device. A comparison for this is lots of sports people paint a dark stripe under their eye and this is to reduce the amount of sunlight reflecting back in, and the principle is the same for these anti-glare masks.

Izzie - Wow! You mentioned that a T.rex is a theropod so will this lead to further studies into a T.rex?

Fiann - Unfortunately, most of the fossils of that particular dinosaur are mostly skeletal; there’s very little in terms of soft tissue remains. Interestingly, there is a tyrannosauroid from the same formation as Sinosauropteryx which is an equally impressive and giant meat eater. This one was 9 metres long and that does have a covering of feathers on it. But, as far as I’m aware, no-one has yet looked at what it’s colour patterns might have been, so there’s a tantalising opportunity to look at what perhaps these giant theropods might have looked like.

19:51 - Could swearing be good for you?

Could swearing be good for you?

with Dr Emma Byrne

As we’re looking at the science of scares for halloween, it’s perhaps appropriate that we’ve also been looking at the science of swears. The idea of letting a naughty word out on air certainly keeps radio presenters up at night, but what actually is swearing, and why do we do it? Georgia Mills spoke to Dr Emma Byrne, the author of the book, Swearing Is Good for You...

Emma - There’s all of this research done on swearing but there’s no standard definition, and there’s not standardised test for swearing either. But you tend to have these repeated common features of swearing, so it’s language that’s often used idiomatically or figuratively. We use it when we are highly emotional, though not necessarily a negative emotion. There’s a lot of swearing that’s used in excitement, or sympathy, or just outright joy and surprise, and also yes, it’s to do with taboos..

Things that are taboos are the things that we don’t feel comfortable or confident speaking about in so-called polite company, and each society has it’s own taboos. So, for example, Japan doesn’t have anywhere near the same sort of toilet taboo that Britain, or particularly North America has, which explains why the poop emojis are so popular. Because poo is just a fun and silly thing in Japan whereas in North America it’s considerably more taboo.

Georgia - It’s this thing that we’re using when we’re highly emotional you said, or to convey emotion. Is there a benefit then to swearing?

Emma - There are actually several. Societally, the biggest benefit is probably that by swearing at each other we’re not actually bashing each other’s brains in. Because if you imagine two tribes of proto humans: one who when one of the hunter gatherers does something completely ridiculous, the rest of the tribe turn on them and bash their brains in, that tribes going to be less successful than a tribe that is able to just literally turn round and swear at this. From the very earliest stages of swearing I think it’s been useful but we also know that it’s good for team bonding, for reducing pain, so many reasons why swearing is useful.

Georgia - I was intrigued by the idea that swearing reduces pain. Time for an experiment with some unwitting volunteers…

Hello, can I borrow you for an experiment?

Volunteer -Yes. Well this looks cold.

Georgia - So we have before us two bowls full of ice water and I’m going to ask you both to put your hands in for as long as possible. You’re allowed to say any word to do with furniture so like chair, table. So when you’re ready to put your hand in start the timer. 3, 2, 1, go!

Katie - Chair!

Izzie - Table!

Georgia - Apart from making my colleagues look a bit foolish, this served to get an idea for how long they can withstand pain while shouting out some non-swear words. Neither lasted that long. So it’s time for round two… Now this time you can swear.

Katie - How much.

Georgia - As much as you like, I’m going to bleep it all out. 3, 2, 1, go!

Katie - Bleep, bleep.

Izzie - Bleep, bleep, bleep.

Georgia - You get the idea. After the two trials Katie managed to keep her hand in for an extra two seconds while allowed expletives and Izzie for an extra 28 seconds. How are you feeling?

Izzie - Really bleep cold.

Katie - Yes, chilly.

Georgia - I know, I know, it’s not exactly lab conditions or a properly controlled experiment but luckily it’s been done by someone who thought about it a little bit more. Richard Stevens published a more robust study in the Journal NeuroReport back in 2009 with some very interesting findings…

Emma - Consistently people can keep their hands in the ice water for about half as long again if they’re swearing and, what’s more, they report that the pain feels less. So it’s not just that they’re feeling the same amount of pain but be more determined to get through it subjectively, it isn’t actually as painful to keep you hand in that ice water while you’re swearing.

Georgia - Do we have any ideas of what’s happening in the brain that could cause this effect?

Emma - We certainly know that swearing is deeply linked to emotions. We also know there is this physiological change in the body when we’re swearing; that the heart rate goes up; that you start to feel a bit more sweaty palmed; that there’s adrenaline being released.

Georgia - Oh right. So it’s something to do then with this kind of adrenaline response to things?

Emma - It may well be the case, but we know that it can’t be as straightforward as the fight or flight mechanism giving you an extra boost. The reason we know that is that if you subject people to a minor amount of pain, the kind that would stimulate a fight or flight response, they actually report subsequent pain as more severe than people who’ve suffered enough pain to essentially cause a freezing or a numbing response. So we know it’s not just as simple as getting people’s adrenaline up, there’s something else that’s going on in that emotional state. There’s some really interesting research to be done to find out exactly what that is.

Georgia - So next time you tread on an upturned lug the swearing might actually be helping you. Perhaps this is why swearing exists everywhere in the world, and perhaps it’s not just limited to humans…

Emma - Some of the most fascinating research I came across while I was writing the book was about chimpanzees.

Georgia - That’s right. It’s not just faeces that chimps are flinging. If you teach them sign language they sometimes fling insults too...

Emma - They definitely invent swearing as they pick up taboos, and dirty was the sign that was used for anything to do with the potty. So dirty is a sign that’s used to do with going to the toilet, going to the potty, anything that had been made a bit filthy.The chimpanzees spontaneously came up with this phrase “dirty good” which meant the potty, which shows that they understand there are some places where excrement is okay, so “dirty good” is the potty.

But “dirty dirty” was used in frustration or as an insult or as a term of disapprobation. Quite often she’d use it against the guy who was studying her, Roger, who would say “come on Washo, let’s do another one of pattern matching exercises,” and she’d go “no dirty Roger”. Or she moved into different accommodation there was, I think, a macaque next door who sort of shrieked at this alarm call when she was put into these new quarters and she signed at it “dirty monkey.” So whenever somebody annoyed or frightened or upset her, she would use “dirty” in the same way that we might call someone a “poop head.”

What is the paranormal?

with Professor Chris French, Goldsmiths London

What exactly is the paranormal? Chris French is a professor of anomalistic psychology at Goldsmiths University in London, and he gave Izzie Clarke and Georgia Mills the lowdown.

Chris - A reasonable definition would be phenomena which could not be explained in terms of currently accepted conventional science. Parapsychologists typically limit their definition of the paranormal to extrasensory perception, telepathy, clairvoyance and precognition, and psychokinesis, and also evidence related to the possibility of life after death, but they draw the line there. The media, and anomalistic psychologists, and I think the general public just tend to use the term to mean anything weird and wonderful. So they would also include things like UFOs, Bigfoot, the Bermuda Triangle, astrology, all of those other things.

If we look at British populations or American, it’s more than half of the population would endorse at least one paranormal claim. If you look at individual beliefs then obviously you get a lot more variation but, surprisingly, about one in four people in the UK believe in reincarnation; about a third believe in psychokinesis; over half believe in life after death. The list goes on.

Georgia - That’s a huge amount of people. Are they onto something?

Chris - Well… who knows. I would call myself a sceptic, but a proper part of scepticism is always being open to the possibility that you might be wrong. I personally don’t believe that any of those things are real, but I’m happy to admit that I could be wrong and maybe new evidence will come along that will make me change my mind. But, at the moment, if I had to bet my house on it I would bet against.

Georgia - Why do you think so many people do believe in the paranormal?

Chris - Well, there are a huge number of factors. One of the things that we’re particularly interested in is the possibility that there are various cognitive biases that might lead people to interpret certain events, certain things that have happened to them in paranormal terms. Thinking that's the only kind of explanation when, in fact, maybe there are other plausible non-paranormal explanations.

Just to give you one example of that: we’re all really lousy intuitive statisticians. We’re not very good at dealing with probabilities and so one aspect of this is that if something happens that is actually just a coincidence. So, for example, you're thinking about someone you've not heard from for a long time and the phone rings, you pick it up and it’s that person. One possibility is some kind of spooky, psychic link between the two of you and another possibility is it was just a coincidence. You think about a lot of people during the day and the phone either doesn’t ring, or the phone rings and it’s somebody - that’s a non-event. It’s inevitable that sometimes you will be thinking about someone just as they ring you.

People often will reject coincidences as an explanation and feel there must be something more going on, so that one fact. There are lots of other cognitive biases that are potentially relevant. But also people do have weird experiences. One of the things that we’re particularly interested in is the phenomenon of sleep paralysis, which is very common in its most basic form. It’s when you’re kind of half awake, half asleep and you realise you can’t move and it typically lasts a few seconds and then you snap out of it. But, in a smaller percentage of people, they get associated symptoms: they might have hallucinations, they might hear voices, or footsteps, or mechanical sounds. Or they might see dark shadows or lights moving around the room, or even monstrous figures. So, it’s not surprising that some people will end up thinking they have actually had a ghostly encounter.

The single most pervasive cognitive bias is confirmation bias. We all find it much easier to accept the evidence for things we want to be true anyway. And I think we’re all rather perturbed at the thought of our own mortality, and even more so perhaps the idea that when our loved ones die that’s it, we’ll never be in contact with them again. We would like life after death to be true and so the evidence to support that idea doesn’t have to be that strong to convince us that it really is true.

32:33 - The Naked Scientists go ghost busting!

The Naked Scientists go ghost busting!

with Brad Mac, Ghost Hunt UK

Now what’s better than a good old ghost hunt to scare yourself silly at this time of year? Well, the bravest of the Naked Scientists team ventured into the dark and eery turrets of Madingley Hall in Cambridge, on our very own ghost hunt. There are a few scary tales surrounding the hall, including many sightings of Lady Ursula Hynde walking up the drive. Izzie Clarke, Georgia Mills and Michael Wheeler teamed up with Brad Mac from The Ghost Hunt UK, to find out what exactly ghost hunters measure, and whether they could find a ghost of our own…

Georgia - We are on the approach to Madingley Hall now. The sun is down, there are crows flying around, and it’s looking very impressive and ever so slightly spooky. So we’re going to see if we find any ghosts. How are my fellow Naked Scientists feeling?

Izzie - Quite excited, but I feel like as soon as I get into a room and there’s a suspicious bump, I’ll be out of there.

Michael - I’m a sceptical scientist, but I keep having to tell myself that I’m a sceptical scientist.

Georgia - Here is our ghost hunter. Hi Brad, nice to meet you.

Brad - We’re getting out the EMF detector. This one will just detect any electromagnetic interferences in the atmosphere. This is a zero so, for instance, if you go near something electronical it should go off. Beep…

Georgia - Oh yep.

Brad - This part here - the top bit of the big antenna - this creates an electromagnetic field in itself. So if anything interrupts that (beep*, anything physical and then that happens quite a lot. It’s quite common for that to happen, which is freaky, especially when you’ve got it out here.

Georgia - So what exactly is it measuring?

Brad - Electromagnetic frequencies, which are what ghosts are meant to be made up of.

Georgia - Oh, right. But also equally any electrical equipment. When I put my recorder next to it it’s going a bit crazy - and also people?

Brad - Let’s have a crack at this later when it gets a bit darker.

Georgia - Then we’ve got your thermal camera, which picks up temperature, obviously.

Brad - This one’s my favourite one. I’ll get the speakers out for full effect… This scans the radiofrequency. You can make it scan through forwards, you can make it scan through backwards, you can make it scan through fast, slow. So spirits are meant to be able to communicate through these frequencies and we can hear that through this little beautiful machine - SP11 spirit box.

Georgia - And equally, if it taps into radio stations nearby we’ll hear that as well?

Brad - Yeah.

Georgia - So the light just turned on.

Izzie - We’re standing here in the dog hole…

Crack!

Brad - That wasn’t us.

Izzie - And there was a really quite loud crack and then the light flickered.

Georgia - Is it an icebox.

Michael - Yeah.

Georgia - Mystery solved.

Izzie - I said I was a logical person and as soon as I hear one little creak I’m like - it’s a ghost.

Georgia - We’re going now into the turret… oh my gosh. We’re entering a staircase

that is wooden and extremely cold. That in itself isn’t spooky because it’s kind of external.

Brad - Is anybody here? Lady Ursula are you here? So the temperatures dropping. Is that somebody there? If that was somebody manipulating this piece of machinery in my hand?

Bump

Brad - Is that a bump. Is that coming from above.

Georgia - Oh was that not you?

Michael - No, no. It’s coming from the inside of the storage room I think.

*footsteps around the room*

Georgia - What!

*footsteps around the room*

Izzie - Oh, I don’t like that.

Brad - Did that just bang?

Izzie - I’m going to say that there’s lots of things going on with the interference. Shouting out - building up tension. You kind of want to believe something was there and that’s why I felt a bit scared.

Brad - Keep the flashlight off.

Georgia - Oh, what. You’re kidding! I’ve been told that to get the full experience I should be in this room, where we’ve had a couple of thumps already, on my own and ask a couple of questions.

Brad - There’s that temperature drop again look.

Georgia - Ohhh. I guess it could be a draft.

Brad - So we’re going to watch for any changes in here.

Georgia - I’m watching for temperature changes and electromagnetic influxes.

Brad - Lady Ursula. It’s dropped right down to two now.

Georgia - Can we leave the door open?

Brad - No.

Georgia - I’m going to lose my mind immediately.

Brad - Once in a lifetime…

Georgia - Yeah, okay. I can do it. I can do it.

So I’m on my own in the room. The door is shut, the lights are off and I’m going to be interviewing a ghost.

If you’re here ghost, could you do something to the EMF reader please. It would make some excellent radio if were to discover ghosts live on air…

Nothing on the EMF reader so far. I’m feeling a little bit cold but it is a room with a chimney in it, and two windows. And the EMF reader is remaining silent.

So, in general, how scared do people tend to get on these things?

Brad - I think it depends on the location. I think if you walk into a location like this, I don’t know about you guys, but for me it felt quite homely. It felt quite warm. I was happy to be here - it’s a beautiful place. Some other places you go to do not feel welcoming at all and feel very, very threatening.

G: That was Brad Mac from GhostHunt UK helping us out there, with the apparently un-haunted Madingley Hall.

Georgia - So what was your verdict? Were you spooked out or are you still sceptical?

Izzie - I was quite spooked at the time. I will put my hands up and say I’m a bit of scaredy cat. But, actually, as the evening went on and we started to pick apart the bumps between us as a team, I wasn’t as scared.

Georgia - I think the most scary moment for me was when that light turned on, but then we realised they were motion activated lights so that made things a little bit more easy to deal with.

38:53 - Dissecting a ghost hunt

Dissecting a ghost hunt

with Professor Chris French, Goldsmiths University London

What equipment do ghost hunters use to detect the paranormal, and what is this equipment measuring? Izzie Clarke and Georgia Mills unpicked their ghost hunting experience with Professor Chris French from Goldsmiths University in London.

Chris - The Earth’s own electromagnetic field is constantly fluctuating. That could easily have had an effect. Any bits of electronic equipment that were around will also affect the electromagnetic field. The idea with a thermal camera is that you will pick up any heat sources. It’s interesting that what happens here, any kind of anomaly whatsoever is taken as evidence of paranormal activity.

The thermal camera or a digital thermometer seems to indicate either an increase or a decrease in temperature, or people report that the feel an increase or decrease in temperature, then that’s taken as evidence of the paranormal. And if the technical equipment actually supports the subjective impressions, that’s taken as paranormal, and if it doesn’t that’s taken as paranormal. Anything that’s slightly odd, even if a lightbulb goes, or some piece of equipment doesn’t work, that’s evidence of paranormal activity. Whereas, in any other context you wouldn't take it as such.

The electronic voice phenomenon is one of my absolute favourites. The basic idea here is that if you take a piece of kit to record, either just place it in reputedly haunted location or record from a radio sent between channels, it’s claimed that you can actually record spirit voices.

There are lots of examples on the internet that people can have a listen to. What you’ll typically find with a lot of these clips is that you can’t actually really make out what they’re saying until someone tells you. They're very short typically, they’re very poor quality. Sometimes, of course, people have unintentionally recorded real living people rather these kind of random background noises that sound a bit speech like.

I did a daytime TV show a few years back where the paranormal investigator was proudly playing his EVP and there’s not doubt at all it really was definitely someone singing Celine Dion songs, and it was definitely pretty terrifying. I just don’t think it was a ghost that’s all. It’s just the power of what psychologists call ‘top down processing.’ When you have a particular expectation, then those ambiguous sounds seem to sound very much more like what you have been told to expect.

Georgia - So many people claim to have seen things like glasses flying round, things like that. Has anything at all like this been captured in a scientific controlled experiment?

Chris - Not in a scientific controlled experiment. There are loads and loads of YouTube videos that apparently show objects moving, pieces of furniture, and so on and so forth. But that stuff is so easy to fake that unless it was done under properly controlled conditions, I really wouldn’t find it very convincing.

Izzie - Now we put this to FaceBook…

Some years ago I was having a very restless night’s sleep and I suddenly felt compelled to look at my bedside clock - it was eight minutes past midnight. The next day I had a call to say my father had died. I asked when? And it was just after midnight. Is that a coincidence?

Chris - It could well be a coincidence. Sadly, people pass away all the time and their loved ones will have looked at clocks. So sometimes, it’s going to happen that the time they happened to look at the clock corresponds to the time. Again, do we know how many times she looked at the clock? Coincidence seems the most likely explanation to me.

I was about 15, staying over at a friends. We were on the sofas in a caravan sleeping. We both didn’t like the dark so we had a light on. I awoke after a few hours to see a man standing in the kitchen area just a few feet away. I saw him in such detail: he wore dirty old ripped clothes, had potato sack type material for shoes tied with string, and I could even see the dirt under his fingernails. I didn’t blink for what seemed like a very long time but once I did, he was gone. So could this have been a ghost? Is there anything scientific regarding apparitions in such detail?

Chris - Could well have been an episode of sleep paralysis by the sound of it.

43:32 - The science behind our monster myths

The science behind our monster myths

with Dr William Sullivan, Showalter Professor of Pharmacology & Toxicology, University of Indiana School of Medicine

It’s not just ghosts that roam our streets trick or treating every Halloween. Vampires, werewolves and zombies are guaranteed to make an appearance. But could science explain some of our monster mythology? Katie Haylor spoke to infectious disease specialist Dr Bill Sullivan from Indiana University School of Medicine, asking firstly how a biologist becomes a monster expert...

Bill - I’ve been investigating infectious diseases for most of my career and I’ve been fascinated with how they induce behavioural changes in animals and people or the organisms they infect. These behavioural changes usually relate to how that pathogen transmits from one organism to the next.

Katie - This idea of infection seems to be one that crosses from biomedical to mythological I guess. Tell us about one of the most prolific or classic monster legends - this is the vampire.

Bill - Yes. The vampire legend originated in the 1600s. It’s a Slavic work for bloodsucker, and it originates from people believing that the undead need to continue feeding on blood in order to stay alive. There have been a number of infections that have been tied to vampirism. Rabies as you know causes aggression and it causes the infected individual to bite. There’s also a lot of foaming at the mouth because rabies causes dramatic throat convulsions that makes it very painful to swallow. But the ties with vampirism is that vampires obviously bite to feed off the living.

There’s another interesting disease called porphyria, which is a blood disorder, in which case people have trouble making haemoglobin. Now that causes toxins to accumulate in the body; it causes the individual to look pale, they have red receding gums which kind of emphasise the fangs in their mouth (the canine teeth). And they also have a rather nasty skin condition where, if they are exposed to sunlight even for short periods of time, their skin will turn red and blister up very quickly just like in the vampire myth where vampires that are exposed to sunlight will start to melt away and die.

Katie - Gosh. Let’s move on then from one monster legend where rabies could be one of the origins to another. Tell us about werewolves?

Bill - Oh yes. Rabies was once described as a disease that strips you of your humanity and leaves only the beast, which is precisely what you think about when you conjure up the idea of a werewolf. But there is also a genetic condition which could have, perhaps, fuelled the werewolf legend. It’s called CHL (Congenital hypertrichosis lanuginosa), and this produces excessive body hair, even hair that’ll grow on the forehead, the nose, the cheeks - it grows everywhere. Unfortunately, these individuals look very much like your stereotypical werewolf but, I hasten to add, there’s no behavioural changes that are associated with this condition. These people just have excess hair.

Katie - It’s really a case of mistaken identity, I guess, in the case of the werewolf legend. But one that really interests me is this idea, I guess kind of Victorian idea of reanimation, and this comes into play when we’re thinking about Frankenstein and Frankenstein's monster?

Bill - I think one of the key experiments was done by Galvani. He was the first person to realise, or discover, that electricity can animate the body. So what he was doing was experimenting on dead frog legs and he was dumping all sorts of chemicals and solutions onto this little frog’s dead leg and nothing ever did anything to it. But when he touched an electrode to it and put a little electricity next to those muscles, they started to quiver and shake and seemingly come back to life.

His nephew took this one step further and got fresh cadavers, criminals who were recently hanged, and put electrodes in pretty much every orifice that you can imagine. The cadaver, once it was charged with the electricity, would thrust out it’s hand; sometimes an eye would open; the body would shake a little. Of course, it wouldn’t come back to life, but you can imagine the people at the time and what they were thinking that no doubt helped inspire the story behind Frankenstein’s monster.

Katie - Frankenstein’s monster: it kind of correlates to the idea of the zombie legend in some ways, these creatures who are stumbling around and eating brains. Tell us a bit about the zombie legend.

Bill - Oh yes; that’s one of my favourites, and it gets back to some of the work that we do in my laboratory. The original zombies that stem out of Haitian religions are when a bocor, which is like, I guess, the equivalent of a priest, would zombify a victim by giving him or her a potion which actually contained paralytic agents. So they would often bury these individuals alive, and it’s been found that these toxins probably kept a person conscious, but he or she just couldn’t do or say anything about it. Then the bocor would go back a day or two later, dig the person up and, voila, they came back from the dead. The toxin had worn off and now they were very suggestive to whatever the bocor wanted to do.

That was the Haitian zombies, but there are a number of real world zombies that are basically parasites that are able to manipulate the brain, or the brain chemistry. Now a little closer to home is toxoplasma gondii: this is single cell parasite that can only complete the sexual stage of it’s life cycle in the belly of a cat, and we don’t understand the reasons for that. This parasite is well known to infiltrate the mammalian brain and, specifically in rodents (mice and rats), it changes their behaviour so that they are no longer afraid of cats and they tend to be easy prey. In other words, the parasite has altered the chemistry of the rodent brain so that it basically can get back into the cat where it can complete the sexual stage of it’s life cycle.

50:07 - Is there a future for paranormal beliefs?

Is there a future for paranormal beliefs?

with Professor Chris Roe, University of Northampton

We heard earlier in the programme that more than half of people in the UK and the US would endorse at least one paranormal claim. But what effect do these beliefs have on our lives, and will there continue to be a need for them in our ever more technological world? Katie Haylor spoke to Chris Roe - a psychology professor from the University of Northampton who specialises in the aforementioned area of para-psychology.

Chris - One of the main theories about why people might have paranormal beliefs is, absolutely, that in some ways it helps us to make sense of the world. Many aspects of the world are chaotic and unpredictable, and good things happen to bad people, and bad things happen to good people, so there doesn’t seem to be any rule or order. But with certain kind of paranormal beliefs, we have this greater sense that maybe, in the end, everything is part of some kind of grand plan.

There does seem to be some evidence that suggests that people are more able to manage anxiety about unpredictable circumstances if they have paranormal beliefs, so that certainly could be a factor.

Katie - But what about people taking advantage of people with particular beliefs, for instance?

Chris - We see a lot of experiences when people are going through a bereavement process, for example, and where they may be quite desperate so find evidence of the continued survival of their loved one. But that could be an opportunity for people to be taken advantage of.

I don’t see the threat here being any greater than in other areas of life, though. And it’s really important to stress that, for example, the mediums that I’ve met tend to be quite earnest people who mainly give up their time for free and they seem to be quite kosher.

Katie - Is there a future for paranormal belief?

Chris - I think certainly as society becomes more technologically sophisticated it becomes progressively easier for people to kind of explode superstitions and myths. So I think certainly there will be shift and a change in the kind of things that people believe in. At the same time, people are still reporting a certain class of experiences: things like premonitions or apparitions and so on that are, maybe, a little more intractable but a little more difficult to explain away, and so I think we’ll have those for a little while yet in trying to understand what’s going on.

Katie - Is there a kind of comforting feeling in a world of what feels like ever-increasing information overload in some ways of there being a place for the unexplained, and that stays unexplained?

Chris - I think people do like the air of mystery about being a human being that comes with some of these paranormal beliefs and experiences. We do feel a little bit shortchanged when we’re reduced to just a biological machine, and neurological mass that’s making all our decisions for us. So I could see there’s a romantic aspect for people wanting to cling to certain kinds of beliefs, but I think what we can do is present that to people and let them see the bigger picture. So here are the factors, here are the possible causes of your beliefs and experiences, but leave the people themselves to make their own decisions.

Katie - This is our Halloween show so I’ve got to ask: have you ever seen any correlation between the time of year and these sorts of experiences?

Chris - One of the main causes of paranormal experiences is people trying to cultivate them. So, if people are out and about and they’re sitting in haunted houses and so on, I think it’s very likely that they’ll have more of those experiences now than at any other time of the year.

But the sobering thing to keep in mind is we run a trial with our own undergraduate students, where we have them come into our university departments one evening late in November to do a haunting investigation and, very often, phenomena occur. People see things, the building creaks, they get cold gusts of wind and things, but the exercise is all about introducing them to how the psychology changes in a familiar place under unusual circumstances. It’s to introduce them to the idea that the mind can play lots of tricks on us.

Katie - So is this the idea of your bedroom at night might seem much more scary compared to your bedroom in the day?

Chris - Definitely. If you actually care to monitor it, you’ll hear that there are as many weird creaks and sounds in the daytime as at nighttime. It’s just at nighttime, they take on this ominous character when, really, it’s just typically the building cooling down and the building just shifting slightly as a result. But, straightaway, that isn’t just a creak, it’s a tap or a wrap or it’s a footstep.

54:32 - QotW - How long could we survive without a head?

QotW - How long could we survive without a head?

Michael - This story seems unbelievable but it is, in fact, true. No ‘fowl’ play involved.

So what does this mean for us? We asked our listeners and Alan thinks that it could be possible, in principle, to keep the body alive with a ventilator and supply of nutrients.

But what does our expert think? We asked Dr Shiva Shanu, Senior Research Associate in Clinical Neuroscience at the University of Cambridge and Lecturer at the University of Kent.

Shiva - The long story is that while some facial reflexes might survive for a few seconds or even minutes, consciousness almost certainly will disappear very quickly, at most within a second or two.

The thing is, immediately following the separation of the head from the body, there will be a sudden drop in blood pressure inside the head. And, as a result, neurons in the brain would very quickly lose the oxygen and the energy they need to keep up their normal pattern of electrical activity, and that’s the activity that sustains cognition and awareness. Hence, without this vital supply, consciousness couldn’t last.

However there is scientific evidence from non-human animals that brain activity might persist for a bit longer than a few seconds after losing your head. But that activity is highly likely to be related to basic reflexes if anything, but not to awareness.

Michael - So your average human wouldn’t survive for more than a second or two. But what makes chickens so special?

Shiva - Regarding the curious case of Miracle Mike, the headless chicken, really the only thing that I would comment on there is the remarkable difference in architecture between the bird brain and our brain. Party because of this, when Mike lost his head, it didn’t really produce the same sort of complete disconnection that we would experience if our head was severed at the neck.

A considerable part of Mike’s brain might well have been preserved, certainly, the bits that control fundamental biological processes like respiration, digestion, etc. That, and the fortuitous and crucial blood clot that prevented Mike from bleeding out, enabled him to survive that long. It’s still quite a unique story after all these years.

So, in summary, we wouldn’t survive very long after losing our head. Though it has been noted that a momentary sensation of pain will precede the loss of awareness and certain death.

Michael - The science of decapitation. You probably thought we’d be too ‘chicken’ to go there! But there it is.

Next week we’ll be sparking some debate with this shocking question from Elizabeth:

Hello Naked Scientists; greetings from South Africa. I was driving on the highway while it was raining and thundering overhead. I remember that someone said a car is a safe place to be in a thunderstorm as it acts as a Faraday cage and the lightening will go around it. Is this true or would the engine shutdown which could cause a huge accident?

Comments

Add a comment